I have a hard time considering myself “a security person” at this time. I’m scared off by intimidating sounding protocols and regulation names, and find it difficult to parse through the legalese of a lot of compliance documents. However, that doesn’t mean that my day to day activities don’t have a direct impact on the overall security profile of my company.

In fact, at smaller companies which may not have a dedicated Security Person, all infra engineers are de facto security people. In other words, some of us have security thrust upon us.

So how can we get started with improving security without titles, and without getting way down into the weeds of various algorithms and threat vectors?

Two pieces of advice: * Focus your initial efforts on the things that are already within your control. No budget? Focus on the free changes. * Remember that small changes over time shift the culture

- Unused Accounts

Identify unused accounts/access in the systems you control and remove or shut them down. This can often be done in a short amount of time with a little Excel magic (or other method of parsing, Excel formulas just have the handy benefit of producing a document anyone you’re trying to persuade can read).

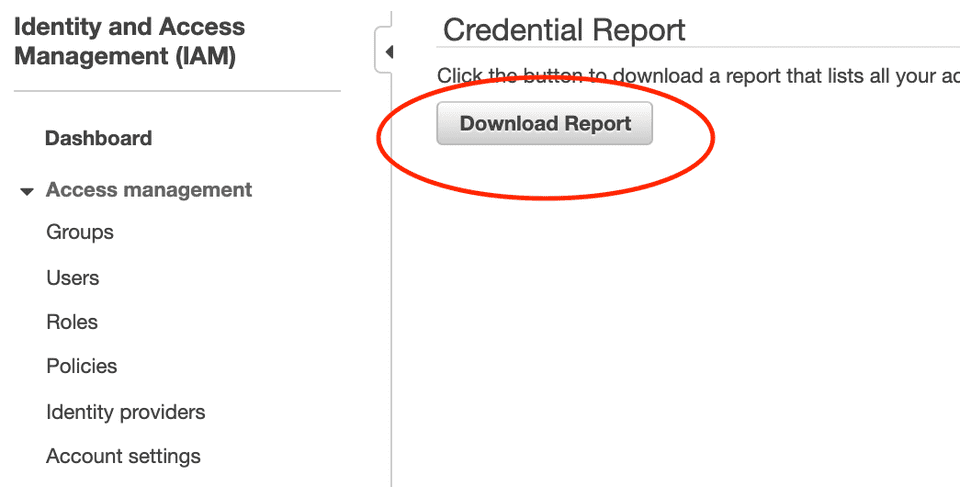

In AWS, use the pre-generated AWS IAM credentials report:

My recommendation is to disable account access for users who have not accessed their account within the last 90 days. Likewise, some developers only regularly access services via the command line and don’t need console (UI) access.

Especially if this is a new initiative, it’s always worth notifying your users that a change is being made to their account and provide them with a path to reverse that change if they do need to access their account in the future. Do they email or slack you directly? Depending on how many devs you support and how often these types of requests come in, you may want to create a ticket template.

- MFA

Enable MFA (multi-factor authentication) wherever you can - your cloud provider, GitHub, your logging system. I recommend familiarizing yourself with how you reset a user’s MFA device and make that documentation really easy to find. Odds are, someone is going to discover their device isn’t synced right during an incident down the road.

- Security group rules

More really useful housekeeping! Admittedly, this one takes a deeper understanding of the systems you support - if you don’t already have friends across a few different teams, you will by the end of this task.

It’s disarmingly easy for security group rules, firewall rules, etc to accumulate that are too open to protect your applications and the business. Worse, ingress/egress permissions are frequently copied over and over, so an overly permission rule in the early days (ah, such freedom! Such chaos!) replicates itself over time.

This is a quick example of identifying AWS security groups with an ingress rule open to the world (‘0.0.0.0/0’):

aws ec2 describe-security-groups \

--filter Name=ip-permission.cidr,Values='0.0.0.0/0' \

| jq '{name: .SecurityGroups[].GroupName, id: .SecurityGroups[].GroupId}'

If you recognize the group and understand its traffic patterns, and therefore, how you could restrict access without cutting off valid traffic - that’s a win! If not, track down the team mates that can help you make those decisions. For unknown, ambiguous or more complex cases, you may need to enable or revisit traffic logging to help you define expected traffic and restrict entry to that pool.

- Password Managers

If your company/team doesn’t already use a unified password manager (1Password, PassPack, etc), identify and advocate for one. Password managers facilitate stronger, more complex passwords. They can also reduce the amount that passwords are insecurely shared between teammates through other channels.

- Explore auditing and get ready for alerting

This last piece is less of a task and more a strong suggestion to get comfortable with the auditing/access logging you will use when an incident comes up. When tensions are high, you don’t want to be focused on the logistics of tracking these down.

Take some tutorials on CloudWatch/CloudTrail (AWS) or Cloud Audit Logging (GCP). Go through your systems in order of importance to the business and locate where those logs are. If they are missing or you can’t find them, this is now officially the best time to start implementing them.

A note on password rotation:

A month ago, I would have put password rotation on this short list. After a congenial but thought-provoking conversation with our head architect and a deep dive into articles that have come out over the last 2 years, I’ve backed off that position. Don’t spend time making all your developers change their passwords unless your auditing team requires it. HOWEVER, passwords should be rotated swiftly in the event of a breach, so step 1 (identifying and disabling access) serves double duty because now you know how to disable access to your systems if that ever comes up.

Remember, security is hard!

Neglecting basic security hygiene makes it harder to react quickly when breaches do happen. However, small changes over time contribute to a culture of security and build a toolset that you can reach into at the critical moment.